Peter Bingham Inchbald was born on the 29th January 1919. His father Pierre, known to all as Peter, had won a Military Cross while serving in the Royal Artillery. Had his mother, née Esmé Lyle Bingham, been born a boy, she would have passed on to him the hereditary Baronetcy of her own father Sir Albert Bingham. The young Peter grew up at Lucksfield, a grand country house in Essex. But he was not a great socialite, rather he grew into a fierce intellectual, passing via Winchester to PPE (politics, philosophy and economics) at Oxford just in time for the outbreak of another war. In between he had learned a love of art and of rock climbing. At Oxford he added a certain amount of modern social philosophy.

Inchbald did not finish his degree course but joined the Army. In due course he found his way to India, where he eventually ended up in Chilàs, an outpost of Gilgit, which itself was an outpost of Jammu and Kashmir. The Chilàsis were Muslim Dards, that collection of mountain peoples whose homes were a series of valleys dotted throughought the geological chaos where five massive mountain ranges meet in a clash of rock and extremes of climate. These valleys were barely accessible and then only on foot during the Summer if you could dodge the avalanches and rock falls, rebuilding the track as you went along. In winter the mountain passes were blocked with snow and impassable. The Dards were as lethal, extreme and unpredictable as the mountains they had made their home. Chilàs was one such mountain valley, which somehow the Indus river had opened up in the utterly chaotic sparring ground of the Karakorum and Himalaya ranges.

Although still in his early twenties and officially a Captain in the British Army, in practice he was the British Raj – the sole white man – in Chilàs, commanding a detachment of the quasi-independent Gilgit Scouts, and his commanding officer was just about the only white man in Gilgit and was doing much the same there. The badge of the Gilgit Scouts is the head of an Ibex, a noble antelope native to that high terrain. Somehow Captain Inchbald wound up with two. He was also the local civil magistrate – judge and jury – dispensing his pronouncements to the fierce and unruly Chilàsi tribesmen. With his beloved golden retriever beside him as a substitute for Western company, when he could Capt. Inchbald would trek with his Scouts for days or weeks on end across his even more beloved mountains.

When India was later partitioned, Gilgit and Chilàs fell right in the thick of the disputed border area. Handed with the rest of Kashmir to India, they and their neighbours rebelled and declared for Pakistan. A bitter and bloody campaign saw neighbours brought back under Indian rule but not Gilgit or Chilàs. Naturally, India wants back what it was given and Pakistan wants back what declared for it. Trouble continues to this day. Perhaps the most astonishing part of the whole business is that Inchbald actually gained permission to revisit the area later in life, while researching a novel that sadly never saw the light of day.

Safely back in London, he went to study at the RA – the Royal Academy – and in due course became a professional painter, dabbling also in silverware. He seems to have got a bit of a name for murals, travelling the country from time to time on one commission or another. It was during this period too that he began to get involved in the family firm, Walker and Hall, and won the competition for the Hull University Mace.

Then a black hole opened in Walker and Hall's top management and Inchbald was asked to take it on full-time. That meant moving North to Sheffield. By then he had a family to drag with him, having married Rosemary Nall, daughter of Sir Joseph Nall who had for many years been the MP for Hume in Manchester. They moved first to a Derbyshire village then to Sheffield itself, to an old farm house barely a mile from Bingham Park, the creator of which had earned the ancestral honour. Did the children want to play there? Did it have a playground or a boating pond, they demanded to know. No it didn't, so they never went and soon forgot its family connection.

Inchbald found in Sheffield a fellow fledgeling designer also interested in silverware, a young David Mellor whom he had befriended at the RCA while in London. Through Walker and Hall, David introduced clean, modern design to the British silverware industry and would go on to become one of the foremost industrial designers of his generation.

The original Garden God

(Private collection)

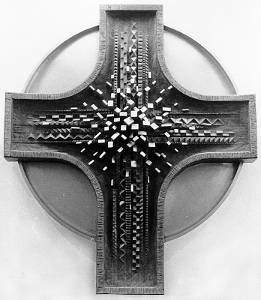

The dark side of the Moon Goddess

During that time, Inchbald became an active member of the Council of Industrial Design, later to become the Design Council. He once made a brief appearance on television in this capacity.

Financial vulnerability is usually close to its peak just as a reborn company is getting into its stride, and Walker and Hall was no exception. A tycoon with a penchant for property and asset-stripping spotted his moment and struck. Inchbald fought hard to save the company, but it was not to be. The resulting British Silverware, a merger of several such victims, became a short-lived fiasco.

Cross (St. Luke's chapel)

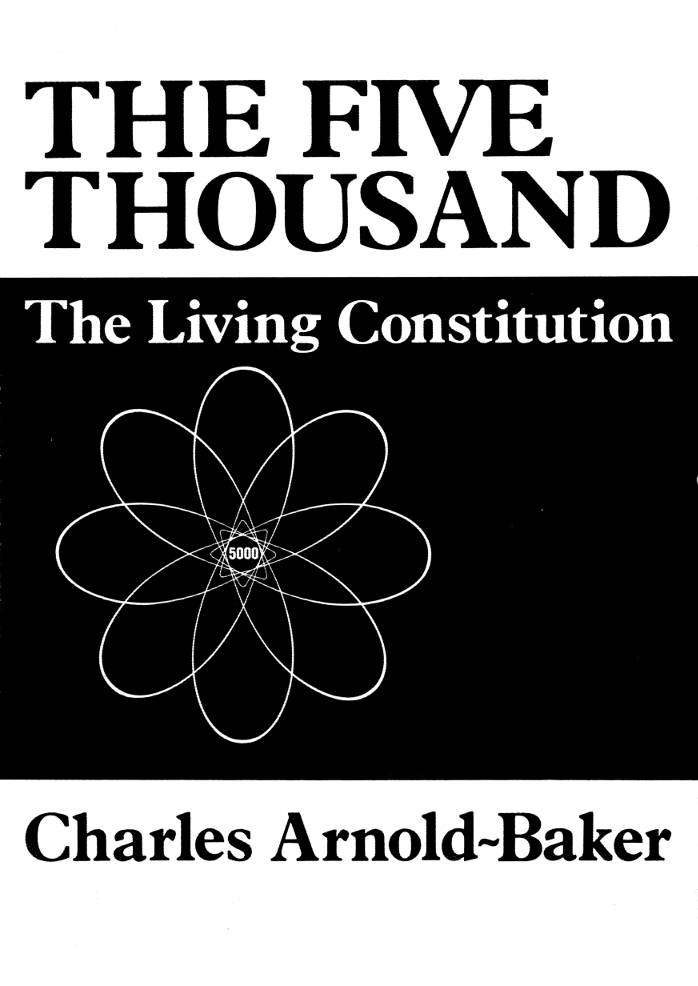

Cover of The Five Thousand

Inchbald found a new role introducing a range of modern door and window fittings at Hope's in the Midlands before yet another merger, this timer with Crittall Windows, threw him back onto his own resources.

He turned back to the arts, this time it was sculpture. A bronze Chapel cross provides the frontispiece to his autobiography.

A Moon Goddess or Garden God stone face resides in Pershore near the Abbey. There is some confusion over the name. The original Garden God was, and still is, a rather smaller bronze statue. The stone face was conceived as his bride, a Moon Goddess. But, when the Pershore Millennium celebrations needed a visual focus outside the Abbey, plans changed and the stone piece found a new home there. The tale involving the two names became garbled, and when the sculpture was moved to a more permanent home nearby some people wanted to call it the Garden God. Inchbald's son Guy recalls him giving his retrosepctive permission for the name change, with some reluctance. Nowadays, both names compete with each other, as can be seen from the captions to the two images here and here. Meanwhile the original Garden God lives on elswhere.

A few other pieces grace private collections. Some years down the line he had suddenly had enough and gave it up.

Along the way he received a graphics commission. His lifelong friend (and godfather to one of his sons) Charles Arnold-Baker was bringing out a second edition of his seminal book The Five Thousand: The Living Constitution and Inchbald designed the cover art. Guy walked in on him as it was nearing completion and remarked on its likeness to the orbits of electrons round an atom. Being that sort of tyke, he commented on the inherent quantum uncertainty of the "electron cloud".

"Yes!" replied Inchbald, "That is exactly what I wanted to capture, the indeterminacy of the whole thing." He and Charles had apparently discussed this at some length. I think it a shame that this imagery is not mentioned in the book, for it perfectly illustrates the nature of the Five Thousand: they are a nebulous bunch, who crystallise into certainty only when a specific decision is made.

During these years he also helped to reorganise the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE), now known as the Campaign to Protect Rural England, on a sound footing, he co-founded the Upton-upon-Severn Civic Society and for many years sat on his local Parish Council.

He turned next to writing. Taking a correspondence course and progressing from short stories and poems to novels, nothing publishable appeared for some years. His Gilgit romance was one of the last to be unpublished, eclipsed in his mind by M.M. Kaye's The Far Pavilions which he discovered while researching his own tale. Then, a minor success. Inchbald turned his knowledge of fine art into Franco Corti, a detective who chased stolen art through a succession of four novels.

Jaded in due course by Corti and feeling the toll of time, Inchbald turned to his autobiography, Jack of All Trades – and his family. He wanted to set down a historical record of what he had seen and done which might interest future generations. Part of this record included the family history, at that time muddled by conflicting stories. Still not quite finished at the time of his death on the 2nd July 2004, it was tidied up and published posthumously by Guy.

Many of the events in this brief sketch of Peter Bingham Inchbald are expanded upon in his autobiography, along with much other material not touched on here. Copies are available, in both printed and electronic (ebook) form, from the list of Lulu books by Peter Inchbald. They are also available through most mainstream outlets.

© Guy Inchbald. Updated 4 July 2017.