More About the Comets

Updated 28 Apr 2024

Since publishing The Comet Racers Uncovered, new information continues to come to my attention, sometimes solving a puzzle or bringing a new one. Some peripheral stories not directly about the Comets also had to fall by the wayside at the time. Here are some miscellaneous stories, facts, puzzles and photos which either did not make it into the book or have turned up since.

Design of the Comet

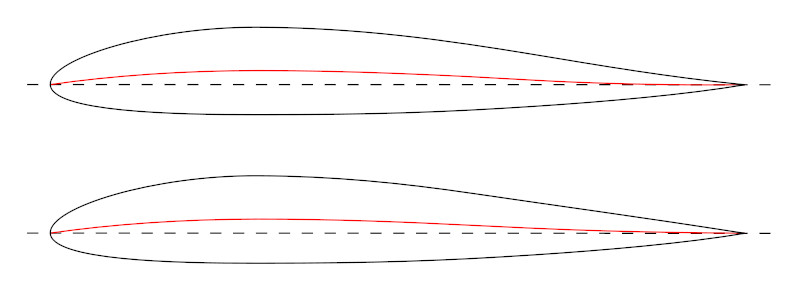

(Top) RAF 34 aerofoil

(Bottom) Modified to flatten concave upper surface

Most aerofoils are unstable in flight and need a tail to steady them. The Comet's wing was based on the RAF 34 aerofoil. It was developed originally for use in tailless aircraft which have no stabilising tail, but its low drag made it popular elsewhere. To make it more stable for tailless types, the top surface dips in towards the trailing edge. There was no room for a drawing in the book; RAF 34 is shown here in the upper profile. The dip makes it awkward to manufacture accurately. So if a designer was going to add a tail anyway, it was not uncommon for them to avoid the problem by flattening the upper surface, as in the lower drawing. This makes it slightly unstable, but as the Comet has a tail that does not matter.

The red lines show the mid point between upper and lower surfaces along the wing, known as the mean chord line. Even with the flat top, the mean chord still dips down a little. On the Comet, this combined with the sharp taper of the wing from root to tip, to create its sudden and vicious stall.

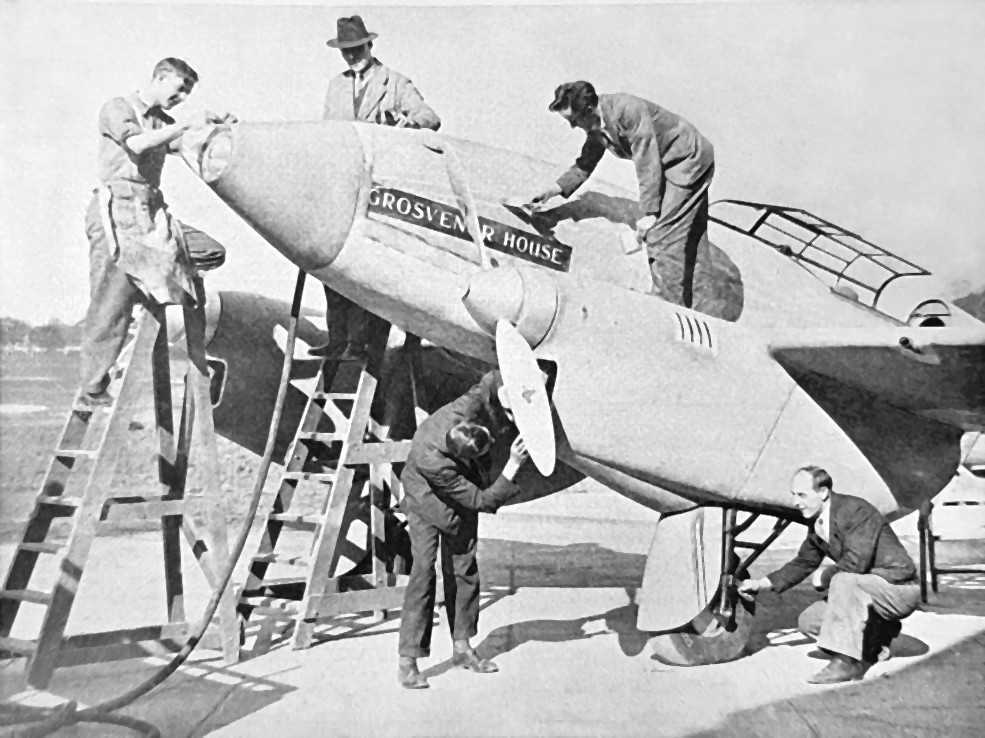

G-ACSS

The first photo below shows G-ACSS when first rolled out for flight testing. Points to note include the pale primer finish with temporary nose art, as present during its christening ceremony indoors. Also the presence of the Ratier propellers which replaced the Hamilton Standards initially flown on the first Comet.When the Comet was given its famous red livery, according to one contemporary de Havilland employee, V.W. Clarkson, the fuselage cheat line was silver and not white as it is today. I should like confirmation that what he saw was not just an opaque undercoat, to stop any pinkness showing through a final white topcoat, but his version of events is entirely possibe. The same silver observation and query apply to the registration markings of green stablemate G-ACSR.

G-ACSS on rollout after christening |

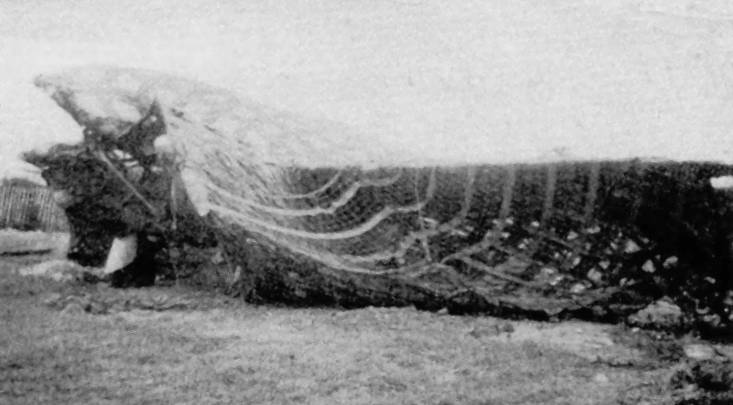

Camouflaged and rotting at Gravesend Airport |

The second photo shows it under a camouflage net, at some point during the late war to early postwar period while parked out in the open and rotting away at Gravesend. Accounts differ as to the timing of events. Some have it that G-ACSS was evicted from its hangar fairly early on, its decrepit remains being rescued by de Havilland in 1943. Others suggest that the plane was turned out a little later on and its rescue came after the end of the war.

The mailplane door hinges

My argument in the book about the mail door hinges does not hold up. A new photograph has surfaced, making it clear that the dark lines seen in some photos cannot be used to identify which side is the hinge and which the fastening. So it is not possible to use them to identify which side the hinge on Reine Astrid is placed, or hence that of H608. Unfortunately I seem to have mislaid my copy, but it shows a similar dark line on the other side from the photo of the same Comet in my book. Other features seen in the various photos, such as the nose cone tips, are not always consistent and changed too often to reach any firm conclusion. So which of F-ANPY or F-ANPZ became H608 and which H609 remains a mystery after all.

Firbeck Hall and G-ADEF

Not long before Cyril Nicholson bought Comet G-ADEF, he had bought Firbeck Hall in Yorkshire and opened it as a private club. He got experienced Comet pilot Campbell-Black to supervise the construction of an airfield for the members' use, and planned to operate the Comet from there. Nicholson planned many record flights and wanted to call his Comet "Firbeck", but was persuaded from the name by Lady Fielding. The Comet nevertheless could be seen there on occasion, as also (it is said) could everyone from royalty to Amy Johnson and Jim Mollison.

It was a glamorous scene while it lasted, but of course Lady Fielding's choice of "Boomerang" proved ill-advised, and the Comet connection faded faster than the club.

The Marendaz Mk III and its Gipsy Six R

When the RAF bought G-ACSS, crashed it and sold it for scrap, Clouston and Tasker bought it for Essex Aero to restore. But they did not want the temperamental Six R racing engines. One was snapped up by Alex Henshaw in the autumn of 1937, for his Percival Mew Gull G-AEXF, and went on to further glories. But what happened to the other one? It appeasrs to have been sold on at about the same time. In my book, I got as far as deciphering a hand-scrawled "Marenda" but ground to a halt through ignorance.

My attention was drawn in 2024 to D.M.K. Marendaz, a WWI pilot turned racing driver and car maker, turned planemaker and flying school operator.

In June 1937 two apparently unrelated events took place: scrap dealer L. Lipton advertised for sale the second Gipsy Six R from K-5084/G-ACSS, along with its Ratier prop [see clipping], and International Aircraft and Engineering Ltd began work on the Marendaz Mk III light aircraft.

At some point not long after that, Marendaz bought the engine off Lipton.

The next March, Marendaz registered the Mk III as G-AFGG and in May showed the almost-complete plane at the RAeS Garden Party, Farnborough. He stated it had a 200 hp Gipsy Six engine and an estimated top speed of 200 mph. These are the same numbers DH gave when they announced the Comet and touted for orders.

The Marendaz Mk III |

The Ratier installation |

The MkIII propeller hub is shown in the closeup above. It is unmistakably a Ratier pneumatic, plus adapter, of the type that went with the Comet's Six R, complete with pressure disc on the nose. Its racing adapter would not have fitted either the original Six I (although DH had provided such for G-ADEF "Boomerang" in 1935) or the then-current Six II. This just has to be the ex-Comet prop and adapter on the ex-Comet engine.

Sadly the plane never flew (certainly not officially - there are always stories). Marendaz ran a flying school, built and flew a prototype Trainer, and was shut down by the war. On 19 December 1940 the assets were sold at auction. They included a de Havilland Gipsy Six. So - who bought the engine and what happened to it next?

The Gipsy Six R from G-ADOD

G-ADOD with original open cockpit

The Gipsy Six R engine, flown in Miles Hawk Speed Six G-ADOD by Ruth Fontes and then Arthur Clouston, was the only one sold separately from the Comets. Thought to have been written off, it turns out to have to have survived after all. When Clouston brought it back after his crash and Tasker declared it worthless, it remained with Essex Aero until that company closed down after WWII and in 1956 its assets were sold off. The engine was then bought by a private collector, along with its log book. The paper trail shows that these have since changed hands more than once, but remain in a private collection. The engine's current owner, location and physical state are unknown.

The Hitler assassination plot

In 1935, de Havilland briefly studied a variant of the Comet fitted with bombs and machine guns, for a secret mission. Was this perhaps the precursor to what followed a few years later? It does at least lend the following story some credence.

After Clouston brought G-ACSS home from his New Zealand flight in 1938, he went back to his day job at Farnborough. There he was contacted by a leading businessman, diplomat and Jew. A plot had been hatched to fit a Comet with bombs and assassinate Hitler during a Nazi parade. It would be disguised with fake markings, fly out beyond Berlin and then turn back for the attacking run so that its origin would be obscured. The whole operation was minutely and carefully planned. Would Clouston be interested? Certainly, the Comet was about the only civilian type on the market capable of such a feat and, as an RAF pilot with solid experience on it, he was perhaps the most qualified of any to take the job on. But he baulked at the idea of being a hired killer and murdering a man in cold blood. He said later that if he had fully appreciated Hitler's atrocities upon the Jewish people at that time, he might have accepted. But, like many, he thought that the press were exaggerating in their usual way. Despite the million pounds on offer, he declined.

More on this extraordinary story may be found in A.E. Clouston; The Dangerous Skies, Cassell, 1954, Chapter XI, and in Matthew Willis; "Death by Comet", Aeroplane, August 2021, pp.30-1.

The Gipsy Six R at Shuttleworth

The Gipsy Six R on display has a story or two to tell. Having first taken G-ACSS to victory in the greatest air race ever, it followed that up with a class record for the 1938 King's Cup, a record which stands to this day and has only been beaten once in any class. But that is not my story here. This story lies under the covers, literally still to be uncovered because contemporary accounts disagree.

These crankshafts were originally made to take a Hamilton-Standard hydraulically variable prop. That would have required a hydraulic oilway up the middle of the shaft, to feed the propeller mechanism. The first Comet (G-ACSP) flew in this condition. When these props were discarded in favour of the pneumatically actuated Ratiers, the oilways were no longer required. An adapter was fitted because the propeller mounting did not fit the shaft and it was too late to rework the engines. This was the state in which G-ACSS won the Great Air Race.

When Henshaw bought this engine, he at first had Essex Aero fit the new Ratier electric actuator. Later, because King's Cup regulations required British manufacture, he had to remove the Ratier system altogether and replace it with one of the new de Havilland props and its own adapter. The DH type was based on the Hamilton Standard system, but smaller. This was the state in which he won his all-time class record.

For display today, this engine has been refitted with a Ratier pneumatic hub and race adapter, of the kind originally fitted. Still with me? Anyway, when Essex fitted the DH system there ought to have been a disused oilway right there, awaiting resurrection, perhaps with an obvious blanking plug to remove. But, according to Henshaw in his biography, there was none and he and Essex had a fine time drilling one out for the de Havilland prop. How could that be? Who's right? What is the truth of the matter?

Essex certainly had to make up a new adapter, as the de Havilland prop did not fit either the Hamilton Standard fitting on the crankshaft or the Ratier mounting. And that adapter would have to have had a new oilway drilled down it. I speculate that Henshaw's memory of drilling out the adapter somehow got falsely transferred in his mind to the engine itself. The only other alternative, that de Havilland reckoned they could drill out the crankshafts while fitted to the plane, is not really tenable (there would be the little matter of swarf in the bearings to worry about, for a start).

Now, here sits the putative engine itself, hiding its secrets under its covers. And there are other details to investigate, such Essex's other modifications, which I will not bore you with here (See the article on Essex Aero in my Aeronauticalia: Highways and Byways of Aviation). A forensic uncovering and investigation is surely called for. And I want to be there!

Update on the survivors

G-ACSP Black Magic has broken through its biggest showstopper, with the acquisition of two Gipsy Queen 30s to replace the previous unserviceable engines. These are slightly longer and heavier, but if anything I would hope that the extra forward weight will help to make it more stable in the air.

G-ACSR Replica G-RCSR has made significant progress. Even better, in a welcome change of heart it has been granted permission to wear the registration markings of the original G-ACSR.

G-ACSS Replica N8XXD remains safe indoors, but is reported to require significant work before it can be made flyable again.

The Galleria replica has not been so lucky. It had been sawn into many pieces for transport to Derby, and was stored there under a temporary shelter. Plans to use its restoration to teach a new generation did not bear fruit, it lay untouched and the shelter degraded and blew to ruins in stormy weather. By early 2024 the replica has deteriorated to such an extent that saving it may not be possible.