Space Planes to Orbit

Re-usable space orbiters are not as easy as they look. Rather than go all-out for a single-stage spaceplane, an incremental approach might prove more practicable. Here is a quick overview of the main issues and a possible design solution.

The challenge of orbital flight

Getting into orbit is hard work. The climb to space is bad enough, but it uses only a fraction of the energy needed for orbital flight. The real work lies in accelerating to many times faster speed than are possible in air, once the craft has reached space. In energy terms, getting to Earth orbit is halfway to anywhere in the Universe.

The first obstacle any spacecraft faces on takeoff is the thick pea-soup atmosphere at ground level. At only moderate supersonic speeds, air pressure on the nose builds up to enormous levels, temperatures soar and the nose weakens so much that it shatters or melts. At higher altitudes the air thins and the higher you go the faster you can fly. In the upper atmosphere hypersonic speeds are practicable, but they are still only a small fraction of orbital speed. So any spacecraft has to start slowly and and steadily increase its speed as it climbs until it reaches space.

Hypersonic flight poses its own challenges, especially in engine design where simply keeping an air-breathing engine from blowing itself out in the blast of air is problem enough. And of course at some point, air-breathing engines must become ineffective and only rockets can take you properly into space.

It is here, on the lower fringes of space, that the real work begins. The speed built up to get this far has to be multiplied perhaps four or five times over to reach a sustained orbit. Everything that you have brought with you is now five times the problem it was before. And if you want to mive beyond a low Earth orbit into say a geosynchronous one that follows the rotation of the Earth, then you can make that six or seven times as hard. Efficiency and weight reduction force themselves onto every smallest aspect of the design.

The thermodynamics of getting into orbit are bad enough. But, perhaps surprisingly, getting down again is even worse. Not only does the aerodynamic drag of the initial flight get turned into heat all over again, but this time the huge amount of kinetic energy built up to reach orbital speed must also be dissipated through heat. Even solid rocks, known as meteorites, melt and explode when subjected to this kind of treatment.

Orbital spaceflight can thus be divided into half-a-dozen main phases, each with its particular demands on the spacecraft:

- Liftoff and subsonic flight in the lower atmosphere. The real heavy-lifting phase.

- Supersonic flight at medium altitudes. Speed is limted by aerodynamic pressures on, and heating of, the craft's nose and leading edges.

- Hypersonic flight in the upper atmosphere. Speed is still limted by the residual atmosphere, which may or may not be breathable by the engines.

- Acceleration to orbit in space. The long-haul stage where the majority of acceleration to orbital speed takes place. Only a pure rocket can work up here.

- Hypersonic re-entry and braking. Most challenging of all, the craft must somehow survive the intense heating it experiences in hitting the atmosphere at orbital speeds.

- Subsonic manoeuvring and landing. The more options you can keep open for landing sites, and the less mobile support operations you need, the better.

A good design will work effectively and safely throughout, and especially efficiently once out in space.

Design principles

There are some basic design principles which apply to any space orbiter.

Most important of all is to try and avoid carrying into orbit anything that is needed only for the first stages of flight. Anything - anything at all - not needed in orbit is dead weight for the hardest part of the trip, the acceleration to orbit. Because this last phase is far the hardest work, any dead weight carried will cause an immense waste of fuel. Indeed, if you try to carry everything in a simple rocket and just add more fuel to lift it then the extra fuel tankage needs more power to lit it, getting you into a vicious circle where the rocket can never reach orbit no matter how huge you make it. You have to find something more efficient. One approach is the multi-stage vehicle, which discards its heavy launcher before reaching space. Another is to gain what help you can from the air along the lower part of the flight path. These approaches can be combined.

Spacecraft experience powerful accelerations and hence strong gee forces. Strong acceleration can dramatically improve overall performance, but at the same time everything has to be strengthened to take the extra gees and that adds weight which both reduces the performance gains and limits the payload design options. The two effects must be balanced out. Then again some payloads, especially humans, cannot tolerate very high gee forces, even in principle. This can limit the technologies available to the designer. Most satellites and other inert payloads are carefully designed and packaged for high-gee flight. Even the most super-fit and highly trained astronauts can manage rather less gee, while ordinary scientists and passengers are more delicate and need lower gee still, posing the greatest engineering challenge. A design approach which suits one kind of payload may be unworkable for another.

As mentioned above, re-entry is hugely challenging, it is not just launching in reverese. Where a craft on its way up enters space at a speed already tolerable in the upper atmosphere, on re-entry it still has much of its huge orbital speed, perhaps even more, and when it hits the atmosphere it is travelling many time faster than when it left. This leads to two problems. The first is heating: how do you stop it melting and exploding like a meteorite? The second is deceleration: it accelerated hard for the whole height of the atmosphere to reach that moderate exit speed, just how is it going to decelerate several times as much to make a soft landing, and how is it going to avoid crushing its payload while it does so?

A key principle to driving down cost is re-usability. Throwing away a space launcher after use and building another one for the next flight is obviously wasteful. But the technology to make a re-usable stage is difficult and hence also both expensive and potentially unreliable. The hardest stage to re-use has in practice proved to be the one which takes the orbital rocket through the hypersonic phase and into the fringes of space.

As technologies evolve, some of the design compromises shift and what suited past generations may no longer be optimal. But that does not mean that the laws of physics change. The most practical answer, at any given level of technical advancement, is not necessarily either the cheapest or the most appealing one.

The traditional design approach to getting into orbit is the vertical-launch rocket. The horizontal-launch spaceplane has long been proposed but never yet realised for orbital flight. A third and seldom studied possibility is the rotary wing, which falls somewhere between the other two. Multi-stage or composite systems have always been essential to any successful solution and also offer the opportuinity to mix-and-match technologies for the different stages of flight. Single-stage-to-orbit (SSO) vehicles must carry so much dead weight into orbit, while still beating the basic rocket equation for orbital flight, that they have yet to progress beyond fantasy.

Step rockets

A rocket is lifted entirely by the blast from its engines, so it takes off vertically. If the engines are not powerful enough to thrust the rocket up hard enough, it will waste time hovering on its exhaust, looking spectacular and burning fuel at a horrendous rate but taking a long time to get anywhere. This is hugely wasteful. For maximum efficiency it needs to get up into orbit as fast as possible. Rocket launches are thus characterised by hard acceleration and high gee forces. Unmanned rockets tend to demand that the payload be tough enough to take such high forces. But a manned rocket has to compromise on the acceleration in order to keep from squashing its crew, making it more expensive.

Even an unmanned, high-gee rocket's speed will be limited at lower altitudes by the intense air pressures of high-speed flight. Accelerate too fast and the nose of the rocket will melt or break up. This puts a practical limit on the acceleration achievable in the atmosphere by all rockets. On the other hand, re-entry sets a minimim level of deceleration that the orbiter and its and payload must withstand. Re-entry is especially hard on the crew. The margin between uneconomic launch acceleration and unsafe re-entry forces is narrow and barely acheivable. Unless you are prepared to waste huge amounts of fuel and money by taking things more slowly, only super-fit trained astronauts can ride a rocket into space and back. This was one reason that the Space Shuttle was more expensive to operate than the preceding series of classic step-rockets.

A simple, one-step rocket is next to impossible to send into orbit: the engineering challenge of getting a single-stage rocket up there is about as impossible as things can get and, even if it were eventually achieved, would be ludicrously wasteful and expensive. Multiple rocket stages - the step-rocket - are essential to make such a rocket practical. Some step-rockets have a separate, unpowered re-entry capsule to bring the astronauts back to earth. But the last powered stage is the orbiter. It is just a big fuel tank with an engine at the back and a small payload at the front and its job is the long haul of acceleration in space. Behind it, a middle stage is needed to lift it up into space where it can work efficiently. This stage will then be discarded so that the orbiter need not take it along. And behind the middle stage is the real heavy-lifter, a huge construction of fuel tanks and giant engines, capable of lifting the upper stages off the launch pad and sustaining them – not too fast now – through the thick pea-soup to a higher altitude where they can get up some real speed. It is so powerful that it must inevitably run out of fuel quite quickly, so it gets left behind even earlier, when the second stage takes over. And that is just as well, because it is also the heaviest of the lot. In fact it is still often not powerful enough to lift everything including its own launch weight and extra boosters get strapped on for initial lift-off.

Spaceplanes

In contrast to a rocket, a spaceplane has wings so it can take off horizontally like an aeroplane and fly up through the air using only a fraction of the fuel needed for a thirsty rocket. It may also use air-breathing engines for the early stages, saving the weight of oxidant tanks. But when it reaches the edge of space its wings can no longer lift and its engines can no longer breathe. A hypersonic jet plane might be able to coast into a brief sub-orbital hop using a zoom climb manoeuvre, but for the long haul to orbit it has no choice but to switch to rocket power.

A great advantage of the spaceplane is that its launch site is less critical. A rocket benefits from careful choice of site to maximise benefit from the Earth's rotation. However a spaceplane can fly economically to wherever suits it best before aiming for space. It is also inherently easier to make re-usable, needing little more than the undercarriage it took off on for it to land safely again.

But the spaceplane has two particular problems to overcome. Firstly, during its horizontal flight in the atmosphere the main fuel tanks are laid sideways, like coke cans that have fallen over. In this position they sag and collapse very easily and must be strengthened. A vertical rocket does not suffer this problem, as a thin-walled cylinder containing pressurised fuel naturally supports itself when stood up on end and needs little extra stiffening. The spaceplane must carry the extra weight of the stiffening all the way into orbit, with all the waste that involves. Extending chines along the fuselage and blending them with the wing roots can help and can also improve the wing characteristics, but it is not a full solution and must still carry a weight penalty. Secondly, as the plane approaches space, those wings and air-breathing engine systems become yet more dead weight. In practice a multi-stage composite plane is still currently the most viable option, though neither the Pegasus air-launched rocket nor the Virgin Galactic SpaceShip has yet made it to orbit.

The single-stage-to-orbit (SSO) spaceplane is in reality little more practical than the single-stage rocket. The weight penalty on the horizontal spaceplane is more severe than most aerospace engineers seem to realise and the SSO plane must also carry along its low-altitude wings and air-breathing engines. In truth it remains more in the realm of science fiction than realistic planning. Not that that stops technologists from dreaming.

One hope is for a hybrid air-breathing rocket engine, such as the Reaction Engines SABRE, which would save so much weight of engines and tankage that the winged, single-stage-to-orbit (SSO) spaceplane becomes possible. The B.Ae HOTOL proposal caused quite a stir in the 1980s.

But possible in engineering terms does not mean efficient or economic. Just think what those advanced engines could bring to an inherently more efficient multi-stage spaceplane.

Conventionally-powered designs already exist which use a heavy-lifting mothership with relatively low-power but very high-efficiency bypass turbofan engines, to carry the spaceplane up above the worst of the air and position it optimally, so that it can zoom up into space on rocket power. But such flights, whether manned or unmanned, remain sub-orbital and full orbital flight from anything other than a rocket launch remains a way off.

You might think thata more advanced, supersonic or better still hypersonic launcher would do better. But in fact it was realised at least as long ago as 1963, when the English Electric design office at Warton was studying horizontal takeoff space launchers, that a supersonic launch aircraft is simply not worth it. The complexity and weight introduced by advanced engines, advanced aerodynamics and high dynamic forces are better spent on making the second stage work a little harder. The faster the launcher can fly, the worse it gets: hypersonic ramjets and high-temperature materials only add to the over-engineering. It is better to keep the launcher simple and lightweight, manufactured from standard materials and powered by conventional high-bypass-ratio turbofans. Its optimum speed turns out to be a high subsonic cruise, much as it does for ordinary long-distance air travel. Unless and until lightweight high-strength, high-temperature materials or a new propulsion technology appears, that is the way it is going to stay.

How much SABRE engines could help the second stage along remains to be seen. In the days of HOTOL, my own take on the idea was for a cut-down HOTOL launched from a subsonic mothership, see below.

Re-entry for a spaceplane is in theory easier, as it has wings it can use as airbrakes and to land gently on a runway. But it still has to take those wings all the way into orbit in the first place, a big penalty as we have seen.

The Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle represented something of a halfway house between the step-rocket and spaceplane, being in essence a step-rocket on the way up and a spaceplane on the way back down. It employed some ingenious compromises to improve low-gee operation and give some re-usability for only moderate penalties.

Firstly, the main engines were all installed in the orbiter and were used throughout every powered flight stage. There was some penalty to this. They were far more powerful than necessary for the small orbiter craft they were fitted to, and one or two of the three were just dead weight during the orbital haul. The penalty was made manageable by limiting them to less than the size needed for takeoff, and making up the difference with extra-large rocket boosters for the first phase of flight.

The spacecraft took off vertically so its main fuel tank and boosters, all fitted externally, did not have the self-supporting problem. But the fuel needed for the orbital burn did need to be supported to some extent once the shuttle orbiter had tilted over in space but was still well below orbital speed.

It was a very original arrangement, finding a tight compromise between the complex design specification for moderate gee and re-usable orbiter against the technologies of the day. However the anticipated cost savings were not realised. It turned out very expensive to both build and operate, and solutions like it are unlikely ever to be seen again.

But the basic idea, of a vertical-launch step-rocket with a re-usable spaceplane as the orbital stage, has been used again successfully, on the Boeing X-37 unmanned spacecraft.

Composite HOTOL

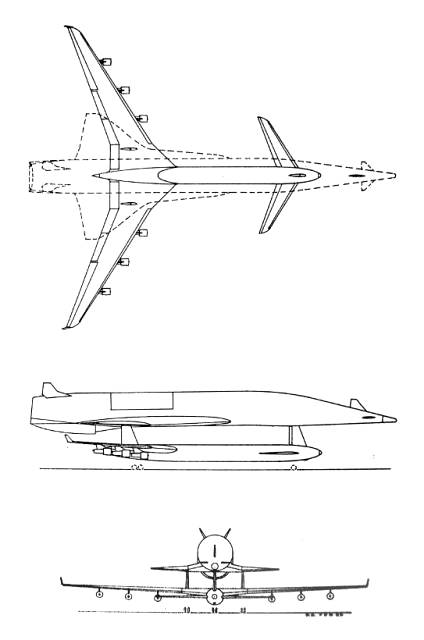

During the 1980s, the British Aerospace HOTOL spaceplane proposal was a hot topic. I reckoned that a "leg-up" from a carrier plane or mother ship, rather like the Virgin Galactic system, would make it more practicable. My article was published in Spaceflight News, Issue 12, Dec 1986, pp 12-15. My original drawing, from which the illustrations in the article were prepared, is on the left.

Much to my surprise, the HOTOL Project and Technical Manager, B.R.A. Burns, took the idea seriously enough to write a letter in reply, which was published in Issue No.25, March 1987, Page 31. He questioned in particular the high capital cost of developing a purpose-designed carrier aircraft – probably quite rightly at this stage of the concept lifecycle. I have other correspondence which shows that this was no off-the-cuff response but B.Ae had already given the idea serious thought before I came on the scene.

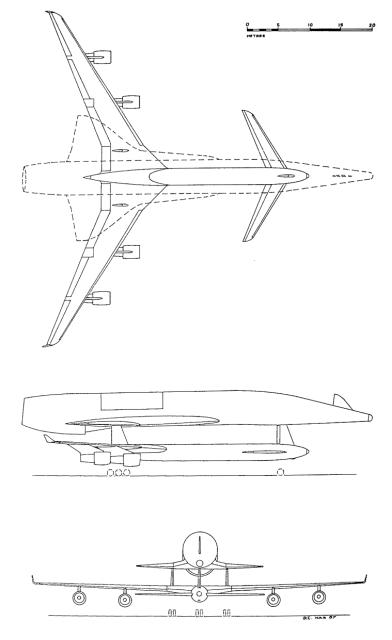

Meanwhile I had revised my design to use some of the more powerful jet engines that were becoming available. This study is published here for the first time, see right.

At that time, Boeing were developing a stretched variant of their 747 jumbo jet. I reckoned it would just about be able to heft a HOTOL – in fact I had stolen its engines for my redesigned carrier. So in response to Burns' letter I dropped my purpose-designed carrier and started to plan a 747 conversion. But then I discovered that Bernard Carr, a professional model maker, had already had much the same idea. The British National Space Centre wote to him on 19 February 1987, commenting; "Your idea of launching HOTOL from an existing aircraft is not new and indeed is already being examined as one of a range of options..." and, "... there are some potential advantages in the subsonic aircraft option ... but it is thought that these may be offset by greater expense. However it is too early yet to come to any conclusions." so I gave up my fringe efforts.

B.Ae's attention was later drawn to the Antonov An-225 Mriya (Dream), built to ferry the Russian Buran space shuttle around. It was huge, bigger even than the stretched 747. When British government interest in the military potential of HOTOL waned, it allowed B.Ae and Antonov to join forces. B.Ae put out a news release, 124/90, on 5 September 1990 announcing a six-month joint study with the Soviet Ministry of Aviation Industry on "Interim HOTOL" (their quotes) which would be launched at an altitude of 9000 metres from the AN-225. Sadly, nothing more than a design study and a few display models (not mine) ever came of it.

And I have since learned of more such studies. As early as 1979 Len Cornier of US company TranSpace was offering a broadly similar composite as a baseline study. The spaceplane was to be a mini-Shuttle, not unlike Hermes or Buran. The mothership was, like mine, to be a custom-designed canard, but it would have the wing of the 747 and eight engines. See Cormier, L.; "Utility of high bypass turbofans for a two-stage space transport", Conference on Advanced Technology for Future Space Systems (08 May 1979 - 10 May 1979), AIAA, USA, 1979. And there have been others, I was certainly not alone in my views.

Composite rotor systems

Another unusual possibility might be to use a rotary wing, like a helicopter, for at least part of the flight. Such a vehicle has characteristics between those of a rocket and a spaceplane. Flying vertically, it does not suffer the need for strengthened fuel tanks that the horizontal spaceplane does, while its rotors offer near-spaceplane lifting efficiency and airbreathing capability. But it is still not an efficient spaceplane: although the Roton project in the US studied it in the 1990s as an SSO technology, its poor lift at altitude left it demonstrably unsuitable for a powered launch vehicle, whether SSO or multi-stage. The operational ceiling of a rotorcraft is much lower than that of a conventional aeroplane, which limits any potential advantages even over a ground-launched rocket. Similarly, its efficiency and range are not large, which limits its ability to position the second stage optimally. Theoretically it might offer some advantage as a first-stage launch booster but that advantage would fizzle out after a few seconds, once a vertical speed of two or three hundred miles per hour had been reached, and there are also huge engineering challenges in building a large enough rotor and balancing a space rocket on top of it. All in all, as a launcher it offers too little advantage over either step-rocket or spaceplane to make up for its severe problems at altitude.

Landing may prove a different story. A rotary wing has yet to be tried in this mode, but it offers some potential advantages. Upon re-entry the rotor would auto-rotate without any need for power and would be flung out into the correct position by centrifugal force. Most modern helicopters can use auto-rotation to land safely in the event of an engine-out emergency. It is light weight: a rotor is stiffened by its centrifugal force and can be made lighter than a rigid fixed wing, while an unpowered rotor system (as in the autogyro) avoids much of the weight penalty of a helicopter. It is true that a rotor is less aerodynamically efficient then a fixed wing, but for the job of slowing descent that does not matter. Roton's later proposals adopted this less ambitious approach, while still aiming for SSO performance.

The autorotating rotor had already been studied by the Entwicklungsring Nord (ERNO) in the eary 1990s for a re-entry capsule atop the Ariane launcher. Known as LAReCa for short, the Large Ariane 5 Return Capsule would first slow itself with a heat shield and then deploy parachutes in the conventional way, but for final landing the parachutes would be discarded and a foldaway rotor deployed. Such a foldaway structure is more practical for a rotor than a fixed wing, because the rotor hinges carry no bending forces and do not need to be locked rigid during flight.

However at orbital speeds a rotor would be difficult to protect from the heat of re-entry, even when folded. Sub-orbital use is probably the best we could expect from it. For an orbital system, this would mean employing the rotor on a re-usable lower stage, rather than the orbiter itself.

Here I consider a kind of hybrid horizontal-launch, vertical-land (HLVL) three-stage design, comprising a mothership or carrier jet aeroplane which takes off horizontally and is fitted with supporting superstructure for a two-stage step rocket that is laid horizontally on top of the fuselage. In this way, the mothership can support the horizontal fuel tankage and absorb the accompanying weight penalty. The second stage forms the rear part of the rocket and has a rotating nose hub with rotor blades folded back down along its sides. The third, stub-winged orbiter spaceplane is mounted in front of it. At altitude the composite craft performs a zoom-climb manoeuvre and throttles back its engines. This points it steeply upwards, temporarily offloading the rocket supports, so that when separation takes place the rocket is now in the correct position to support itself.

Could this all take place at supersonic speeds? Possibly, but not without proving the concept in a subsonic generation first. Any supersonic separation would need to ensure that shock waves generated by one stage did not impact and destabilise another. But more mundanely, the engineering and cost advantages for the second stage would not be particularly enormous, while the engineering challenges and cost of a supersonic carrier certainly would be.

On separation, the second-stage engines fire and the rocket continues into space where it separates again in the usual way. The second stage falls tail-down until it meets the atmosphere. Its rotors then swing out and stream up behind it and, because of their slight inherent twist, begin auto-rotating. As they gather speed they swing outwards again, greatly increasing the air resistance and acting as air brakes. Soon the rotors can fully support the craft and conventional cyclic pitch control can be used to steer it onto its landing pad. At the last moment they angle up even more, expending their last energy in slowing it for a gentle landing. The Space Shuttle flared its nose up and slowed its descent at the last moment in just the same way. If airbreathing rockets such as the SABRE become available, the second stage can be significantly shrunk and lightened.

The third, orbital stage has small fixed wings for use as a shield and airbrake on re-entry, just like the Space Shuttle. But, relieved of the Shuttle's extra engine and fuel management systems, the orbiter is smaller and cheaper. It could also exert even gentler gee force, allowing its wings to be even smaller, although this might need several passes through the upper atmosphere and back into space to shed enough speed and heat before it could begin its final descent.

Some of the manoeuvres necessary to this scenario would have been far too dangerous to consider in the past. For example during the steep zoom-climb the weight of the upper stages would add to their drag to create a significant pitch-up moment. This would suddenly end when the engines were cut, ready for the upper stages to be released. Traditionally such drastic pitch changes would have been extremely dangerous and difficult to handle. But modern digital control systems have overcome all that, and safe operation would not be a problem.

Could a rotor system be adopted for the orbiter too? Possibly, but there are some difficult problems to overcome. A rotor orbiter would look much the same as a rotor second stage and for re-entry would also fall tail-down until it met the atmosphere. But it would differ significantly. Physically it would need a broad heat shield to swing closed across the engine nozzle during descent. Such a shield presents a real design challenge because it must be large enough to provide sufficient deceleration while also being strong enough to support the magnified weight of the rocket under that deceleration, all without weighing much itself or obstructing the landing feet. Assuming that to be possible, it could perhaps be a clamshell split down the middle or a multi-petaled flower. "Ouch!" You might think, "Won't the hypersoinc plasma of re-entry eat through the gap?" Well, remember that the Space Shuttle had heat shielding tiles across its underside. On its landing approach, doors opened in the shielding to reveal undercarriage fitted with ... rubber tyres! That's right, if rubber tyres can be protected by opening panels, I don't see why a rocket engine can't be.

Heat-shielding a set of spinning rotors would be a lot more difficult. Exposed to the hypersonic plasma stream, spinning would only increase their local speed through the air and make things worse. It would be necessary to keep them folded away, tucked behind the main heat shield, until the worst of the speed had been dissipated; this was the approach taken by LAReCa. The craft might at first fall very obliquely, skimming the outer atmosphere to steadily convert its orbital speed into heat and stream it away. This allows it to be relatively gentle on the astronauts, as conventional vertical deceleration has to be extremely fierce. To achieve this flight mode safely it would need either a novel shape that is aerodynamically more stable than a conventional vertical-entry capsule, or a high-speed electronic control system. Only once it had slowed to speeds comparable to the sub-orbital second stage would it steepen its angle of descent and deploy the rotor.

Another quirk for the astronauts would be a need for the seats to tilt ninety degrees relative to the takeoff position, so that they would still sit upright once back under gravity. The Space Shuttle did exactly that the other way when changing from vertical to horizontal flight. But the swivelling mechanism adds unwelcome weight. Also, for a cargo lifter it might not be possible to bring back large payloads shaped to be launched horizontally, as they might not survive being tipped over to land vertically. To be truly practical, an orbiter should take off and land in the same attitude.

Overall a rotor orbiter would be a far more risky technology to develop and may well prove impractical. Certainly, the rotor concept should be proven in a sub-orbital module where the flight regime can play to its strengths, before attempting orbital re-entry.

Updated 31 Aug 2022